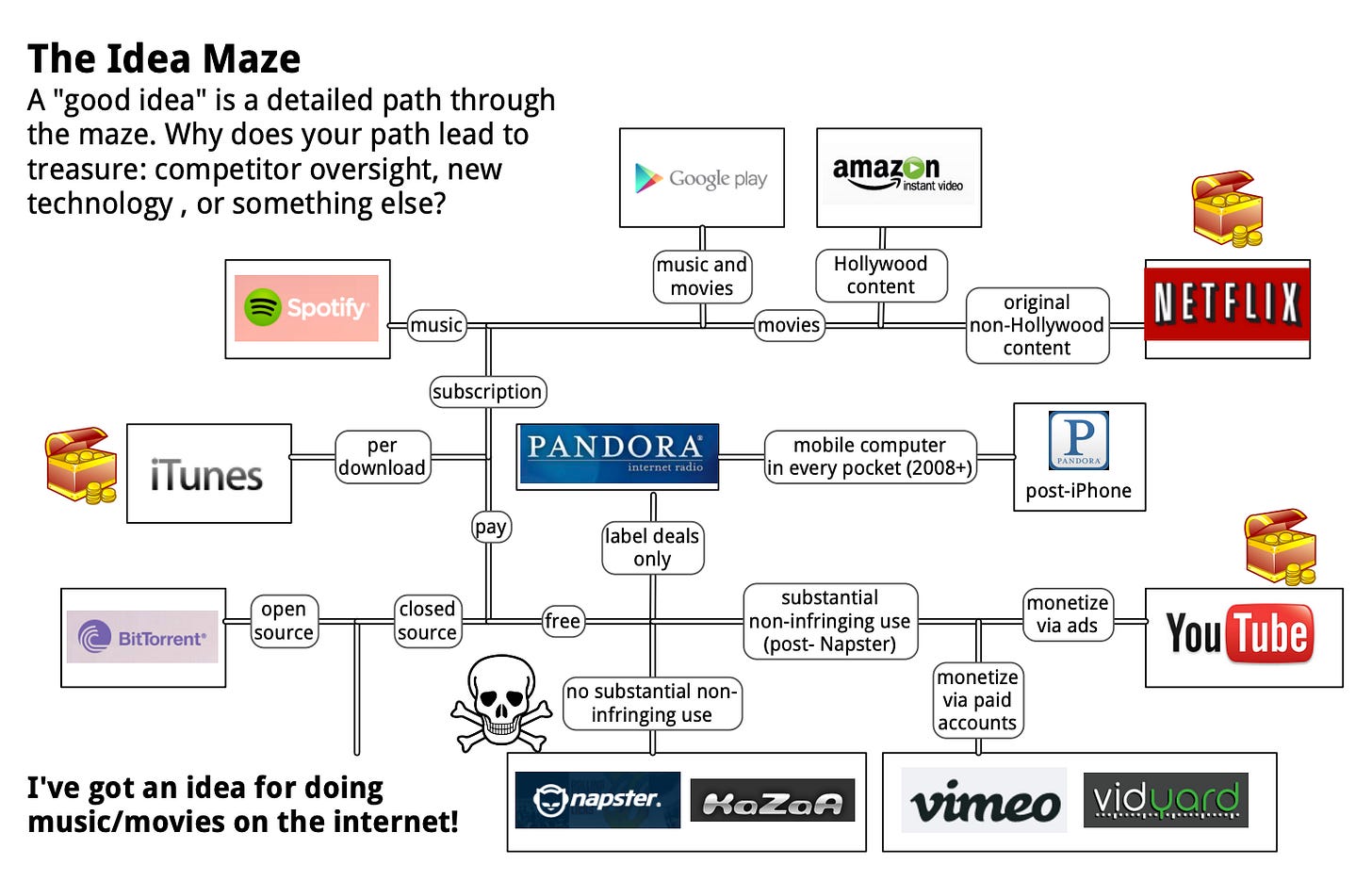

My old employer had a post about The Idea Maze — a concept about how to navigate the idea space of startups.

Basically, it means can you explain all the decisions that have gone into the strategy and placement for your respective startup idea. Can you walk through your thinking in a way that shows you’ve thought about all the different paths you could take (and why you’re taking the one you are)?

A good founder can explain what paths they are(n’t) taking, why they are(n’t), and in the case that they’ve tried other paths, they’ll explain what they learned from those dead ends.

The maze is a great metaphor because it invokes the idea of wandering and discovery. It also isn’t necessarily clear that you will find your way out. Maybe there isn’t an exit to the maze! You can’t really know until you go in and start exploring.

The Idea Maze comes from Balaji Srinivasan’s lecture notes on entrepreneurship, and was subsequently popularized by Chris Dixon’s succinct blog post.

Chris gives a good perspective on the framework (forgive the long excerpt):

In other words, people often fall in love with their particular product idea and run full speed at executing it, without understanding the history of the category, context of other failed attempts, etc. These might be important clues that might explain why this particular idea hasn’t yet been built, and the dangers posed along the way.

The pop culture view of startups is that they’re all about coming up with a great product idea. After the eureka moment, the outcome is preordained. This neglects the years of toil that entrepreneurs endure, and also the fact that the vast majority of startups change over time, often dramatically.

In response to this pop culture misconception, it has become popular in the startup community to say things like “execution is everything” and “ideas don’t matter”.

But the reality is that ideas do matter, just not in the narrow sense in which startup ideas are popularly defined. Good startup ideas are well developed, multi-year plans that contemplate many possible paths according to how the world changes. Balaji Srinivasan calls this the idea maze:

A good founder is capable of anticipating which turns lead to treasure and which lead to certain death. A bad founder is just running to the entrance of (say) the “movies/music/filesharing/P2P” maze or the “photosharing” maze without any sense for the history of the industry, the players in the maze, the casualties of the past, and the technologies that are likely to move walls and change assumptions.

All of this is practical, and is a great way to understand a founder’s intentionality.

However I find this insufficient in the American Dynamism Cinematic Universe. You can’t just walk through the Idea Maze, you need to be a Maze Historian.

We seek Maze Historians — people that know the history of every single maze, who made it, when they made it, why they made it, what materials they used, what tradeoffs each one had, etc.

You need this because the biggest tension in the ADCU is this Buffett quote:

“When a manager with a reputation for brilliance tackles a business with a reputation for bad economics, the reputation of the business remains intact.”

Most of these industries haven’t been touched by tech yet, and there are very good reasons for why that’s the case. But if you think you can suddenly waltz in, you’re going to be sorely mistaken.

Building in these categories requires intentionality because you can’t spray and prey, you need to be sniper shotting. And the best way to learn what target you need to aim for is by knowing the history of a category so completely that you are truly encyclopedic.

Two final points: First, this can’t be a purely academic endeavor. You need to go out and actually act upon your plans. Actions produce data, and without this combination you won’t be able to realize your vision. Most of the ADCU does not have easily parsable data, which means you have to go out and find things out for yourself. You can’t sit back and read a textbook to understand the U.S. lumber industry.

And lastly, it’s worth noting that it takes a lot of time to build a replete level of understanding. Some investors I talk to pride themselves on knowing so much about a given category. They put say ~100 raw hours into learning about a given market. That may sound like a lot, but that’s about a week’s worth of time for a really good founder, which means they’ll know substantially more than you will. And if they compound that over a sustained period of time, they’ll reach net new knowledge for the category.1

One example: this year I was with one of our founders in Japan where they were talking to fishing experts. This founder proposed an idea and the fishermen proceeded to tell him that they had never thought of that before. In this case he went from knowing everything to generating new knowledge and insights that will drive the category forward. That’s what happens when you’re truly encyclopedic.

That’s the ultimate goal: know enough about the category that you put yourself in a position to actually pioneer it yourself. You transition from being a maze historian to being an explorer and pioneer.

It takes time to build this level of understanding. There aren’t any shortcuts; as an investor, you know when you meet someone with replete knowledge of something. That doesn’t mean they’re an expert, oftentimes they’re a relative outsider that may be enough of an insider to get people to tell them what they need to know.